Table of Contents

Modern Deevie (ModD) Middle Deevie (MdlD)

- Phonology and Orthography (this post)

- Vowels

- Consonants

- Phonotactics

- Allophony

- Transcription Examples

- Morphophonology

- Consonant Sandhi

- Vowel Sandhi

- Resolution of Vowel and Consonant Clusters

- Morphology

- Morphological Processes One

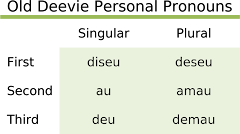

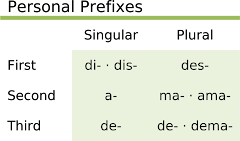

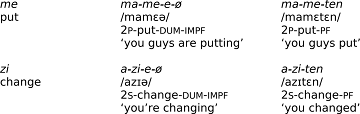

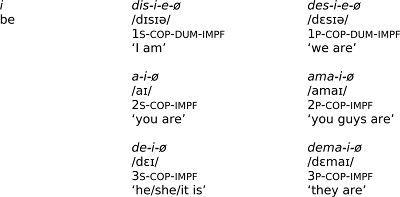

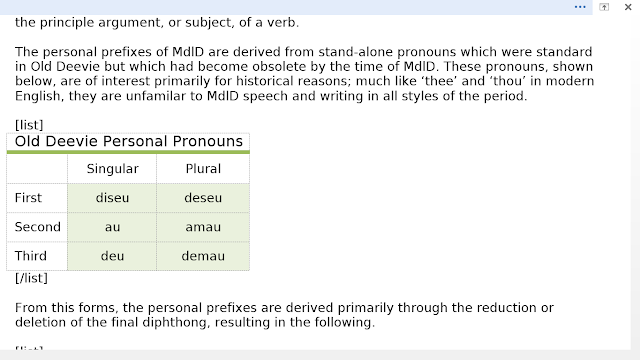

- Personal Prefixes

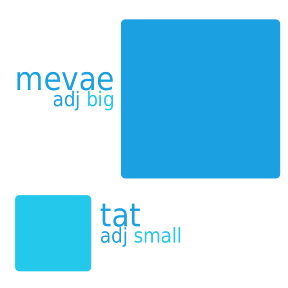

- Word Classes

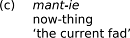

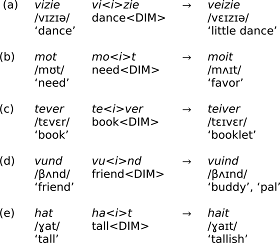

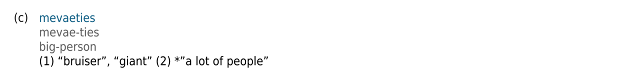

- Nominalization

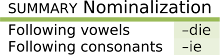

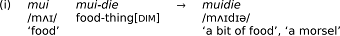

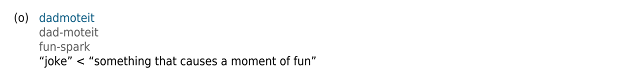

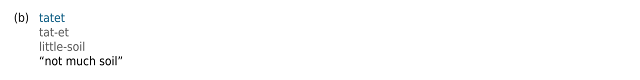

- Diminutives

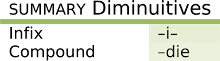

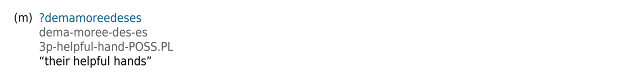

- Possessive Constructions

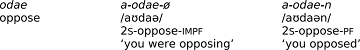

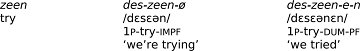

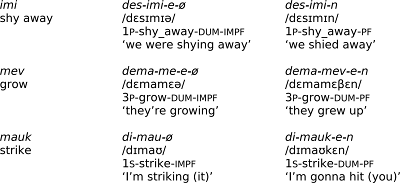

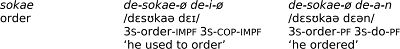

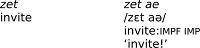

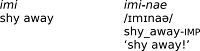

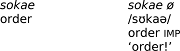

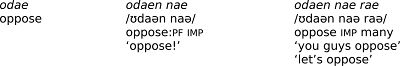

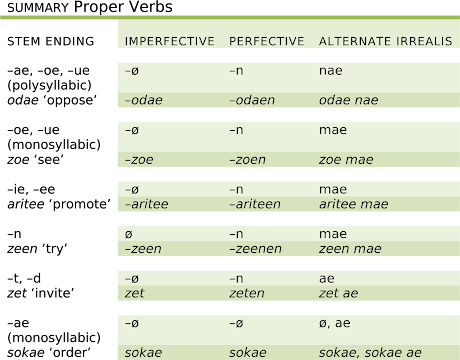

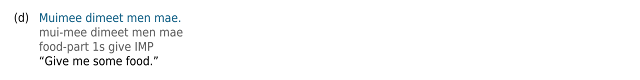

- Verb Conjugation

- Morphological Processes Two

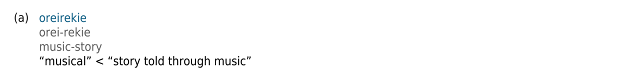

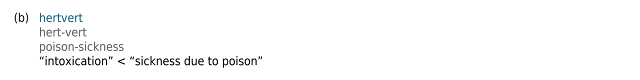

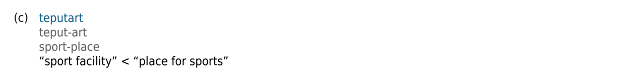

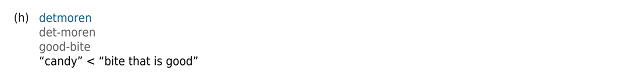

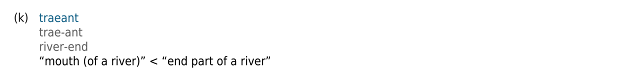

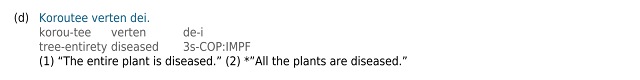

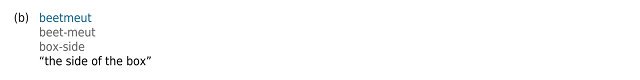

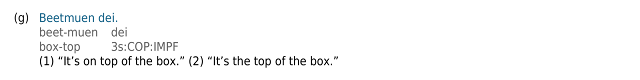

- Compounding

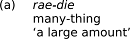

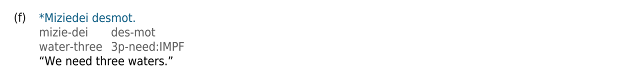

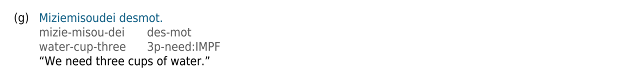

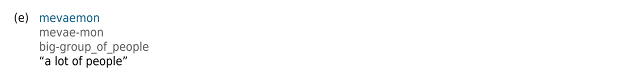

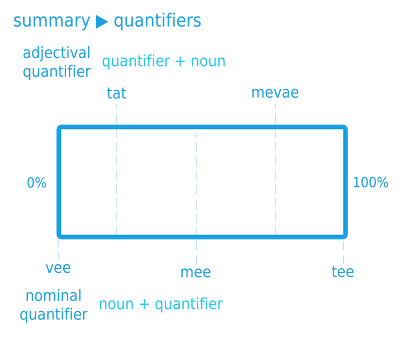

- Quantification

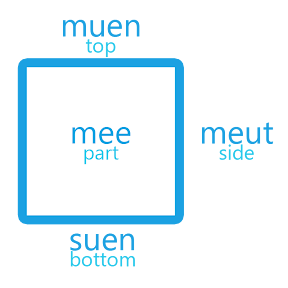

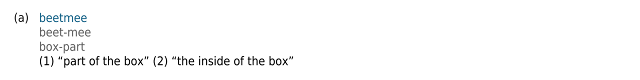

- Spatial Relations

- Pronominals

- Morphological Processes Three

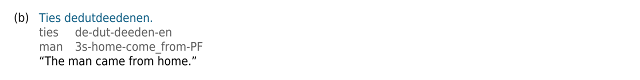

- Compound Verbs

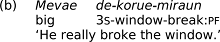

- Object Incorporation

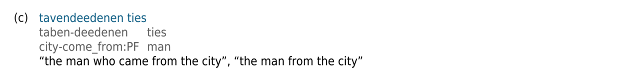

- Relative Clauses

- Morphological Processes One

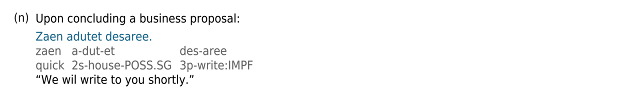

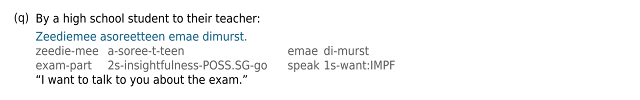

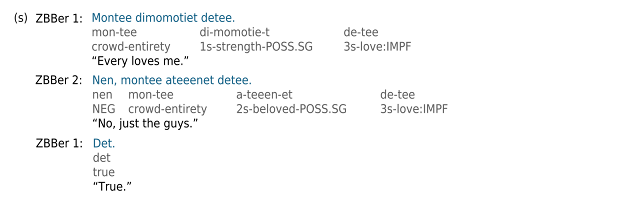

Hey guys. As we usher in the new year, what better time to actually set a tone of productivity alongside other resolutions? In that spirit, this thread will serve as a place for me to (hopefully) finally document all the myriad changes that have occurred in Deevie /zɛvi/ (Deevie /zɛβɪ/1) since the last time I posted about it here (which, incidentally, was also at the end of December), at which point it was still named Dautian and was rather anglocentric. The language is not currently associated with any particular conworld or conpeople, so the discussion will sadly stick to a purely linguistic point of view.

In order to more fully understand modern Deevie, particularly its orthography, we will first take a look at the historical development of the language from the point at which the current writing system began to be codified. I will refer to the language of this era as Middle Deevie (MdlD), which contrasts with the language as spoken and written today, Modern Deevie (ModD). As with English, Deevie orthography has changed little in the intervening period, relative to pronunciation, a stasis which is responsible for creating what is an equally convoluted relationship between phonemes and graphemes. The name of the language itself is a simple example: following palatalization, affricatization, and fricativization, the once-plosive /d/ is now pronounced as the corresponding fricative, /z/. The reason for oddities like this should become evident as we follow the language through time time time time

Ahem. Anyways, here we go.

Middle Deevie (MdlD)

Phonology

VOWELS

- ▶ Monophthongs

▶ Diphthongs

- ▶ Syllable Structure

The structure of a Deevie syllable is as indicated in the diagram below. Parentheses indicate optional elements, such that a syllable may range from as little as a single vowel, at its simplest, to sequence of five phonemes, at its most complex. The rules that govern acceptable choices for optional elements will be described in detail shortly.

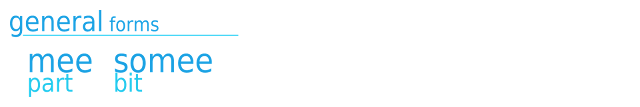

▶ Notation

When discussing phonotactic constraints, featural notation will be used to mark the classes to which consonants in a group must belong. For the most part, I have followed the notation seen in most of the literature, but I summarize my practice here for clarity:

- The features of an individual segment are enclosed in square brackets [].

- A [+] indicates the presence of a feature whereas a [−] indicates its absence.

- Greek letters are used to co-index features such that any elements with the same letter have the same status regarding said feature, while elements with different letters have opposite statuses. For example, [α voice][α voice] corresponds to either [+ voice][+voice] or [−voice][−voice], whereas [α voice][β voice] corresponds to either [+voice][−voice] or [−voice][+voice].

When writing out the corresponding phonemes, a vertical bar | is used to delineate segments. Phonemes between the same bars represent different possibilities for the given segment. A double vertical bar represents a syllable break. For example, n | t d || t d | r corresponds to any of /nt.tr/, /nt.dr/, /nd.tr/, or /nd.dr/.

Manner of articulation is written separately as the overarching pattern of a given sequence. For example, we might refer to a two consonant of fricatives and plosives as Fricative | Plosive, and specify [α voice][α voice] to say that the fricative-plosive pair must agree in voice.

Finally, note that when only one set of square brackets appears for multiple segments, those features apply to each of the segments. That is to say that, when considering a cluster of so many segments, a single [+alveolar] is equivalent to [+alveolar][+alveolar][+alveolar]…, and so on. Also, the abbreviation NR is used when there is no additional restrictions on a cluster (general rules, such as coda restrictions, still apply).

▶ The Onset

All consonants can occur as the sole consonant of an onset. Legal clusters are as follows.

▶ The Nucleus

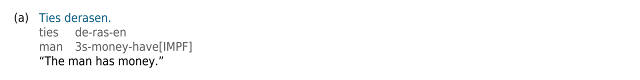

The nucleus consists of one monophthong or one phonemic diphthong. No other vowel clusters are allowed. The only other restriction is that monophthongs may not occur word-finally; alternatively, one can say that a word-final nucleus must contain a diphthong. Observe the examples below.

▶ The Coda

The only consonants which may appear in the coda, whether alone or in a cluster, are alveolar consonants with the exclusion of the voiced alveolar fricative /z/. Thus legal coda consonants include /n t d s r/ and the following two-consonant cluster combinations of them.

▶ Medial Clusters

Deevie distinguishes between intramorphemic medial clusters, which are the clusters that occur within indivisible lexical items, and intermorphemic ones, which occur between morphemes during compounding and affixation. In general, intramorphemic medial clusters are much more restricted than those that occur between morphemes. Indeed, they can be summed up quite simply as seen below.

Wait, one more thing. The tables above show legal two-consonant medial clusters. But from syllable structure, medial clusters can be as long as four segments long. Medial clusters which have more than two consonants, such as /mɛst+kaə/, are legal if, at the morpheme boundary, the last consonant of the coda and the first consonant of the onset form a legal two-consonant syllable cluster. The given example, /mɛst+kaə/, is legal because /t+k/ is a legal intermorphemic medial cluster. Similarly, the intramorphemic medial cluster /men.traə/ is legal because /n.t/ is legal. On the other hand, because /t+d/ and /t.d/ are not a legal medial clusters, neither are /mɛst+daə/ or /mɛst.daə/.

- In addition to the featural notation outlined above, the following abbreviations will also be used when describing allophonic rules.

The following alternations occur both morpheme-internally and between morphemes. Those marked (W) also occur between words. The order of precedence is as listed here.

- Nasal Assimilation (W)

N → [α place] / __[α place]

Nasals assimilate to the place of articulation of the following consonant. - Fricative Devoicing (W)

F → [−voice] / [−voice]__

Fricatives are devoiced when following voiceless segments. - Bilabial Fricatives in Consonant Clusters:

- Bilabial Fricative Retraction (W)

[F +bilabial] → [+labio-dental] / [−bilabial]__

Bilabial fricatives are retracted to labio-dental position when following non-bilabial consonants. - Bilabial Fricative Lengthening

[F +bilabial] → [+long] / [−fricative +alveolar]__

[−fricative +alveolar] → ø / __[F +bilabial]

Sequences consisting of a non-fricative alveolar followed by a bilabial fricative are realized as a geminate bilabial fricative.

- Bilabial Fricative Retraction (W)

- Rhotic Retraction

T → [+uvular] / [+velar]__

Trills become uvular2 when following velars. - Vowel Rounding:

- Rounding of Monophthong Vowels

[+back] → [+rounded] / [+bilabial]__[+bilabial]

Back vowels are rounded between bilabials. - Rounding of Rising Diphthongs

[+back] → [+rounded] / [+bilabial]__[+close][+bilabial]

[+close] → [+rounded] / [+rounded]__[+bilabial]

For diphthongs that rise from a back vowel to a close vowel, both target vowels are rounded when the diphthong falls between bilabials. - Rounding of Centering Diphthongs

[+back] → [+rounded +long] / [+bilabial]__ə[+bilabial]

ə → ø / [+rounded]__[+bilabial]

For diphthongs that start from a back vowel and move to the center, the back vowel is rounded and lengthened and the schwa deleted.

- Rounding of Monophthong Vowels

- Ellision of Plosives

P → ø / O__O

Plosives are ommitted between obstruents.

- Nasal Assimilation (W)

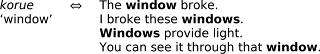

Now, we could just go on transcribing everything in IPA, but that would leave out all the fun that can be had by contemplating an orthographic mess, and we can’t have that now, can we? As stated in the introduction of this grammar, MdlD is, by definition, the period at which the writing system still used today was first being standardized, at which time most letters were assigned a one-to-one correspondence with phonemes.

(On a sort of technical note: it would be more naturalistic to assume that Deevie has its own writing system and that the orthography described here is merely a Romanization. On my part, it would require little more effort to simply state this to be the case, but the thing is that I’m really not sure if I’ll ever get around to actually designing a script for Deevie. For this reason, I tend to think of the Romanization as the actual script, and you might as well, also. How? A wizard did it.)

While Deevie is not associated with any conworld in particular, some of the history in the development of the orthography assumes certain social factors. In particular, the early contradictions that exist in the orthography come from the competing practices of two schools of writing: one is the style of the economic and political powerhouse of the Deevie linguosphere, which is responsible for promulgating the standard language through pedagogical practice and economic necessity, whereas the other is the style of the literary and academic centre of the land, where printing presses would have first churned out popular works at the start of the age of literacy. While the influence of (let’s call it) the capital would prove substantial and its speech become the basis of the standard spoken language, the printing presses of literary-land would be determine several aspects of the written language. Yes, that’s it. Anywhom, while the finer details will have to be fleshed out another day, the key thing to take away from all of this is that there were two competing orthographies that eventually came together to bring forth ModD writing.

CONSONANTS

- The representation of consonants is fairly straightforward and is equivalent in both capital and literary styles. In the table below, phonemes are shown in black and graphemes are shown like ⟨this⟩. Where no grapheme is shown, the grapheme is identical to the IPA symbol.

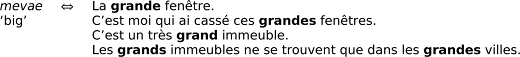

VOWELS

- The monophthongs /ɪ ɛ a/ are written with their closest corresponding Roman equivalents, that is ⟨i e a⟩. The two styles diverge on the graphemes for /ʊ ʌ/ however, and in fact take contradictory positions. As such, in MdlD texts, we see ⟨o u⟩ being used nearly interchangeably to represent back vowels: the capital style uses ⟨u⟩ /ʊ/ ⟨o⟩ /ʌ/, whereas the literary style inverts the two, having ⟨o⟩ /ʊ/ ⟨u⟩ /ʌ/, and there’s quite a bit of confusion in between.

In each style, closing diphthongs are represented by the sequence of graphemes that corresponds to the spoken sequence of graphemes. Thus /aɪ/ is written ⟨ai⟩, /eʊ/ is ⟨eu⟩, and so on. Once again, back vowels are a lost cause: /ʌɪ/ can be either of ⟨oi ui⟩, in the capital and literary styles respectively, while /ʌʊ/ can be any of ⟨uu uo ou oo⟩, although the literary style is inconsistent in its derivation of diphthongs and tends to use ⟨u⟩ to indicate /ʊ/ as the second element of a diphthong, such that we most often see ⟨uu⟩ in literary style texts and ⟨ou⟩ in capital-style texts; the forms ending in -o are very rare in published works and are in fact a mark of semi-literacy that is referenced either exasperatedly or mockingly in many style guides of the period.

There is harmony, at least, in the writing of centering diphthongs. All styles use ⟨e⟩ to mark the schwa, such that /aə/ becomes ⟨ae⟩, /ɪə/ becomes ⟨ie⟩, and so on. In summary, vowels are written as shown in the table below. Where multiple symbols appear, the ones to the left of the dot are preferred by the capital style, and the ones to the right, by the literary style.

In this grammar, MdlD words will be written in the form that corresponds to their modern forms. Consider /zʌʊ/ “smile”: in period texts, we see all of zou (capital-style), zuu (literary-style), zuo (?), and even, though rarely, zoo (???); but because the modern form of the word is zuue, this grammar will use the second of the four. Contrastingly, /mʌʊ/ is written mou, among other choices, because its modern form is moue and not *muue.

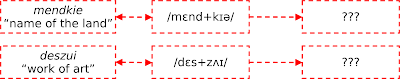

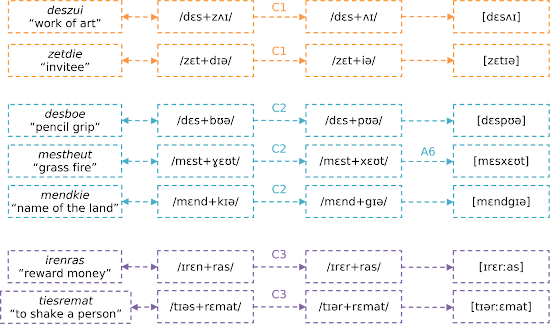

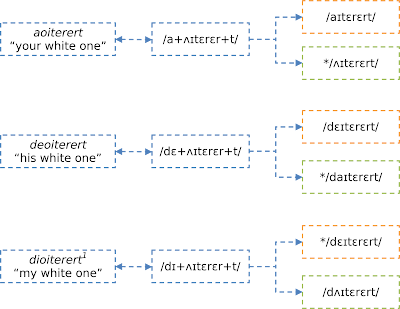

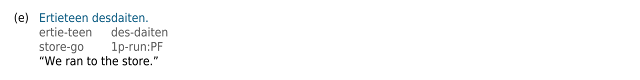

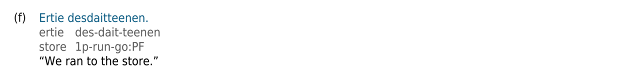

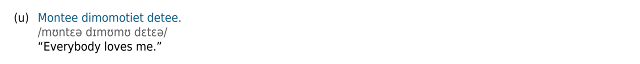

- We will now combine all that we have discussed on phonology and orthography to give the broad (phonemic) and narrow (phonetic) transcription of several example words. In the examples below, the plus sign + indicates a morpheme boundary. Numbers above arrows refer to the corresponding allophonic rules.

Footnotes

- Thanks to Whimemsz for helping me to catch a previous error. The pronunciation given is for ModD, as per the discussion below, but I had previously transcribed ⟨v⟩ as */v/ rather than /β/.

- I had at first incorrectly said that trills became velar when following velars. Sure, it seemed more intuitive at the time, but given the dispute over whether velar trills are even possible (the IPA doesn’t think so), it was an odd statement. Thanks to Qwynegold for catching this one.