Desired feedback:

1) Editing: Does it make sense? Are there errors?

2) Testing exercises in sections 2 and 3

3) Testing out section 6 on a conlang produced by language contact

I've copied the text below. However, I strongly encourage people to visit the actual post, where it has been formatted to be easier to read and navigate.

§0 Introduction

In this post, my goal is to tackle a plausible explanation for a problematic feature of Marshlandic: subject pronouns. As described in an earlier post, the subject pronouns are a, na, ta, ya, derived from Arabic personal verb prefixes. This is ultimately a remnant of very preliminary work on Marshlandic, before I'd developed much of a history or society.

The social make-up of the early Old Norse-Arabic bilingual community (hereby referred to as the Forebearers) would not be conducive to this sort of linguistic development, nor was it a particularly easy development to explain apart from social factors either. Such problems arise when you begin constructing a language without first developing the society.

From the beginning, a few things are clear. The borrowing of morphological features would have required the Forebearers of Marshlandic to have a good understanding of Arabic. They likely would have been able to communicate in Arabic without having to translate from Norse to Arabic in their heads. The personal verb prefixes would have had to be reanalyzed in their function in order to replace native subject pronouns. At some point in the development of Marshlandic, they would need to be able to replace Norse subject pronouns, and by this point there would have to be few barriers between the verb prefixes and the subject pronouns.

The most unfortunate part about this particular problem is that morphological borrowing is relatively understudied. This is due in part to the difficulty and improbability of morphological interference in comparison to other aspects of language. Indeed, for a long time linguists were skeptical (and some old school linguists still are skeptical) that morphological features can be borrowed at all. Nonetheless, we will venture into what theory we do have.

I'd like to offer my apologies in advance for the density of this post. Because of the amount of material I will be covering, it will not be very accessible to those who are not very knowledgeable about basic linguistics. If you come across this post and would like more explanation on anything, feel free to comment, and I will get back to you as soon as possible. Over time, I will also attempt alleviate the density by adding exercises to each section to help the reader's brain process the information provided.

I wish to begin by referencing my favorite book on language change: Campbell's Historical Linguistics: An Introduction. While it can hardly be said to be thorough, and its approach incomplete in the eyes of sociolinguists, the book serves as a comprehensive yet quick reference on existing theory about the structural processes of language change. You will hence see me reference this work often.

§1 Processes of Morphological Change

To understand morphological borrowing, we must first understand how morphological change happens in the first place. Below is a quick overview of mechanisms behind morphological change according to Campbell:

a) Boundary change: Underlying linguistic processes, such as semantic loss or analogy, can cause the development of a new allomorph (that is, a variant of a morpheme) by causing changes in boundaries. An example of loss is in the word acknowledge, wherein the a- had an historical function but later became part of the stem. The words an uncle were originally a nuncle, but through analogy the morphological boundaries were reanalyzed as an / uncle. Similarly, peas originally meant a single pea, but by analogy the -s was reanalyzed as the plural marker.

b) Change in placement: The placement of a morpheme can change again in conjunction with other linguistic processes, especially due to semantic pressures. Campbell uses an example from Nahuatl: in čoka-ti-nemi, -nemi marks a verb as ambulative, meaning an action is done in multiple settings. In another dialect of Nahuatl, the allomorph -nen- can be found in ki-nen-palewiya, coming before the verb instead of after, and taking on a habitual aspect. He further notes that this change in placement was analogical, having semantic commonalities with other morphemes in that position.

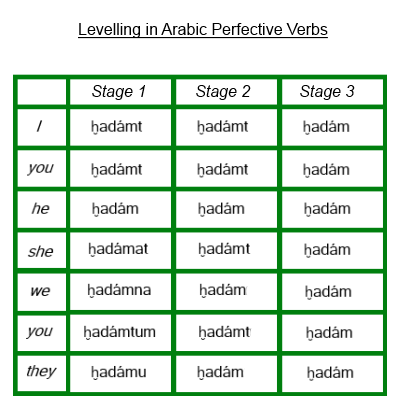

c) Leveling: This is a type of analogy wherein morphemes essentially give way to a more common morpheme with similar functions. In English, this occurred in verb conjugation according to person. In most cases, person is no longer marked in English verbs due to leveling.

d) Loss: The loss of morphemes causes other morphemes (or other linguistic features) to take their place. An example in Standard English is the loss Old English -ende, whose function was replaced by another morpheme -ing. (This differentiation, however, still exists in part in lower spoken registers of English: the pronunciation of -ing as -in' is actually the remnant of -ende).

e) Grammaticalization: A lexical morpheme, carrying semantic content, can become a functional morpheme with grammatical purpose. English -ment in entertainment ultimately was a word of its own, mente, meaning "in the mind (of entertaining)." It lost its meaning as "mind" and instead became a nominalizing suffix.

f) Exaptation: This is a process in which a morpheme has become virtually defunct and is co-opted for a new purpose.

g) Change of Type of Morpheme: The following processes create new morphemes out of older ones. They are listed and described in brief.

Free to Bound: When an independent word becomes dependent on other words, such as with mente > -ment.

Bound to Free: The opposite phenomenon of the above, but occurs much more rarely.

Root to Affix: Similar in nature to Free to Bound.

Affix to Root: Similar in nature to Bound to Free. For example, ex from ex-boyfriend.

Affix to Clitic: This is somewhat similar to Affix to Root in that clitics function independently of a word, but are attached like an affix. A popular example is 's in English, which was once a genitive suffix. That is, it marked the possessive on nouns. It still has this function, but it is now independent of nouns. It can, for instance, occur after an adverb or a clause: somebody else's hat; the queen of England's navy.

Derivational to Inflectional: Somewhat straightforward, this is when a morpheme that originally changed the meaning of a word becomes a morpheme that changes grammatical attributes. It is somewhat rare in nature.

Inflectional to Derivational: The opposite phenomenon of the above.

Derivational to Derivational: As an example, English -ly originally derived adjectives from nouns. Later it became used to derive adverbs from adjectives. (Note, although adjectives, nouns, and adverbs are discussed primarily in grammar, changing from one part of speech to another is a semantic process, not a grammatical one).

Inflectional to Inflectional: Similar to the above, but between inflectional morphemes that inflect grammatical properties, such as direct object or subject.

§2 Directionality of Morphological Change

Campbell also details some emerging theories on directionality -- the order in which morphological change typically occurs. Generally, these theories need more testing and research, but they seem to show some promise to Campbell:

1) Unidirectionality hypothesis: More lexical morphemes tend to become more grammatical morphemes.

2) Postpositions usually become case suffixes, rather than the reverse.

3) The partitive develops from an ablative. "Eat some of the pizza" would come from "eat from the pizza."

4) A derived form will take over the primary function, and marginalize the older form into secondary functions. Brothers/brethren is one such example.

5) Analogical leveling is more likely than analogical extension.

6) In leveling, non-existent endings tend to be replaced by existing endings rather than existing endings just dropping off.

7) Watkin's Law: Third person singular is the basic form in the development of the verb paradigm.

8) Indicative verbs more easily change other verbal moods rather than vice versa.

9) Present tense verbs more easily change other tenses than vice versa.

Exercises (26 March)

1) What theories of directionality have implications for nouns?

2) What theories of directionality have implications for verbs?

3) What theories have implications for the type of morpheme change?

4) Construct a hypothetical situation to demonstrate each theory with English.

5) Construct a hypothetical situation to demonstrate each theory in a constructed language.

§3 Morphology in Language Contact

Now that we have looked at the limitations of morphological change within a language, let us now review some general theories of morphology change between languages.

1) Sakel & Matras (2007): borrowing is motivated by cognitive pressure toward efficient use of language to communicate, not only according to the speaker's linguistic repertoire, but also to the audience's linguistic repertoire.

2) At the same time, social acceptability of the repertoire conditions the outcome. (Sakel & Matras 2007).

3) According to Sakel & Matras (2007), borrowing is affected by: intensity and contexts of exposure, structural similarities and differences, and inherent semantic-pragmatic properties.

4) Sakel & Matras (2007): The more morphologically complex a lexical item be, the less likely it will be borrowed.

5) Sakel & Matras (2007): Semantic transparency facilitates borrowing: plural markers, diminutives, agentive derivational markers, classifiers are among the easiest morphemes to be borrowed.

6) Sakel & Matras (2007): Nominal morphemes denoting peripheral local relations (for example, expressing "between," "around," "opposite") are more likely to be borrowed over core local relations ("in," "at," "on").

7) Sakel & Matras (2007): Adpositions are more easily borrowed than bound cases.

8) Sakel & Matras (2007): Although linguistic constraints don't necessarily preclude them from being borrowed, bound case, gender, tense, person markers and unbound person markers are the least borrowed morphemes.

9) Field (2002), Sakel & Matras (2007): Order of borrowability of morphemes: nouns, conjunctions > verbs > discourse markers > adjectives > interjections > adverbs > other particles, adpositions > numerals > pronouns > derivational affixes > inflectional affixes

10) Field (2002): Another order of borrowability: content item > function word > agglutinating affix > fusional affix

11) Sakel & Matras (2007): Order or borrowability of verbal morphemes: modality > aspect > future tense > other tenses.

12) Sakel & Matras (2007): Order of borrowability of modal morphemes occur in order of the subject's control: obligation > necessity > possibility > ability > inability > volition.

13) Principle of System Compatibility (PSC): Field (2002) states that "any form or form-meaning set is borrowable from a donor language if it conforms to the morphological possibilities of the recipient language with regard to morphological structure."

14) Principle of System Incompatibility (PSI): This theory, also from Field (2002), closely resembles the above theory: "no form or form-meaning set is borrowable from a donor language if it does not conform to the morphological possibilities of the recipient language with regard to morpheme types."

15) Principle of Morphosyntactic Subsystem Integrity (PMSI): Seifart (2012) proposes this theory as a restriction on morphological borrowing. He claims that it is easiest and most probable to borrow morphemes when they are paradigmatically and syntagmatically related. More or less, entire morphological paradigms will be borrowed into a language rather than borrowing one single morpheme.

Exercises (26 March)

1) In what ways can you combine the theories on the order of borrowability? Try your hand at making the most efficient combination(s) possible.

2) How would you describe PSC, PSI, PMSI in your own words? or Construct a situation that demonstrates these theories.

3) How do social associations play into borrowing? Can you draw a parallel to a lexical example provided in the post on domains of borrowing?

4) Consider the point about cognitive pressure from Sakel & Matras (2007). How does each theory relate back to this?

5) Demonstrate each theory by using a constructed language to borrow morphological features into English.

§4 Application to Marshlandic Subject Pronouns & Verbal System

So let's look back and see which of these rules and tendencies apply to the derivation of Marshlandic's subject pronouns from Arabic person verbal markers. Those rules and tendencies that may inform the intermediary steps of the derivation are highlighted in blue font. Rules and tendencies that suggest this is a tough or unlikely scenario will be highlighted with red font.

2.d: Semantic shift: To become detached from the verb and become an independent pronoun, the person marker would necessarily have to lose its semantic connection to the verb and take over the semantic qualities of the pronouns.

3.4 Derived form will take on primary functions, and retained older forms will be used only for secondary functions: In Marshlandic, the new nominative pronouns <a, na, ta, ya> take on the primary functions, while the original nominative pronouns <tui, had, hån, tumj, tav> function primarily as emphatic pronouns.

3.8 Indicative verbs: The indicative mood is most susceptible to change, so it helps the case of the Marshlandic derivation that the change occurs in the indicative mood. With the indicative mood being the default verbal mood, it can easily influence other moods. This could influence semantic shift through analogical changes extending the indicative person markers to other moods. However, the morphemes in question were not originally tied to mood anyway.

3.9 Present tense verbs: The present tense is most susceptible to change, so it helps the case of the Marshlandic derivation that it occurs in the present tense. Occurring in the default tense, it can easily influence other tenses. This can influence semantic shift through analogical change extending the present tense person markers to other moods.

4.1 Pressure toward efficiency: In order for the paradigm to be borrowed in the first place, the Forebearers would have needed to have the person markers fully within their repertoire, as would their day-to-day audiences. The borrowing must have increased cognitive efficiency as well.

4.3 Intensity of contact, Structure, and Properties: Instead of explaining each of these individually, I will simply say they are all covered elsewhere in this list.

2.g.2: Bound to free: This would be a case of bound-to-free morpheme change, an existing but rare phenomenon.

3.7 Watkin's Law

4.2 Social acceptability: Not only must it be within their repertoire, but they must be free of negative connotation.

4.5 Semantic transparency

4.15 PMSI: Since the morphemes are, in fact, paradigmatically and syntagmatically related, they would likely be borrowed together, or quickly one-after-another.

3.1 Unidirectionality hypothesis: This sort of change goes against the typical direction of language change.

4.8 Least borrowed morphemes: Bound person markers are among the least borrowed morphemes between languages.

4.9,10 Order of borrowability: The order of borrowability also suggests that it would be particularly tough to borrow these affixes.

4.13, 14 PSC, PSI: While the morphemes have rather similar equivalents in Norse, their structural position will have made it hard or even impossible for them to have been borrowed without a change in placement (2.b).

§5 Development in Marshlandic Subject Pronouns & Verbal System

It is probably safe to conclude that the beginning of this development is unnatural, and subsequent developments unlikely though possible. Because I would like to retain this feature in Marshlandic, I am going to use an easy cop out: in linguistics, you will find counterexamples to most rules and tendencies, and not all phenomena are explainable due to lack of information on transitional steps. Perhaps, for instance, there was some sort of alignment in the structure of the Andalusi-American Arabic and Vinlandic Norse morphemes. In this case, the borrowing would still be unlikely, but it would remain possible. At this time, however, I do not wish to make that presumption. Instead, I will try to explain the development in accordance to the rules above as best as possible.

1. The Forebearers probably began by simply codeswitching verbs.

* Yadʕū hann í masgid-i? "Is he praying in the mosque?"

Pray(Arabic) he(Norse) in(Norse) mosque(Norse)

Note that mosque is labelled as Norse, because it had been fully borrowed into Norse and is not the result of codeswitching.

2. The verbs were then borrowed as an adjacent paradigm to the existing one. This differs from the previous step in that it requires large-scale borrowing of verbs with few remaining native synonyms into the Norse system, so that a large corpus of verbs using Arabic conjugation exists. Note also that this step requires the weakening of the Nordic linguistic tradition, so that the original manner of expressing these verbs in Norse is lost.

3. The two tense systems quickly converged functionally and semantically. The Norse future tense, constructed with an auxiliary verb, fell out of use as the present tense converged with Arabic's imperfective present-future tense.

He will build me a boat - *Hann mun smíza mésh bát > Hann smíza mésh bát > Hann smizj mésh bát

4. As the present tense came to indicate actions extending into the future, the Norse past perfect became semantically extended into some present tense functions in order to emphasize actions completed in the present. This construction later became the Marshlandic perfective present tense.

Hann esh smíz mésh bát - 'He has built me a boat' > 'He just built me a boat' > 'He is (finishing up) building me a boat'

Hann esh skotj spjót - 'He has thrown a spear' > 'He just threw a spear' > 'He throws a spear'

5. Auxiliary verbs then became the impetus of the Norse verbal system, with only the imperfective present-future not using an auxiliary.

6. Arabic verbs now distinguished between only the imperfective present-future and the non-present-future. The auxiliary verbs slip into the Arabic verbal system to differentiate between the perfective tenses: subjunctive, past, perfective present, and perfective future. These verbs qualified the Arabic perfective.

Al gozi esh ḫadam al løjusøjumann - 'The elder gives service to the chief." (Perfective present)

Al gozi skal ḫadam al løjusøjumann - "The elder will (at that time) serve the chief." (Perfective future)

Al gozi vash ḫadam al løjusøjumann - "The elder served the chief." (Past)

Ef sé al gozi ḫadam al løjusøjumann, falˤal hann al goza - "Were the elder to serve the chief, he would favor the elder."(Subjunctive)

7. Verb stems began to undergo levelling due to redundant person-marking.

*Vésh smízum mésh bát > Vésh smízw mésh bát 'We build me a boat'

*Þésh smízi mésh bát > Þésh smízum mésh bát > Þésh smízw mésh bát 'You guys build me a boat'

8. This happened likewise -- perhaps even first -- in Arabic perfective verbs.

9. What resulted was a clear stem in Arabic verbs unmodified by any affixes. By analogy, the person marker of the imperfective present-future became detached from the verb.

*Þu yaḫdum al løjusøjumann > þu ta ḫdum al løjusøjumann 'You serve the chief.'

10. As the Norse verbs levelled, these person markers began to be applied to the imperfective present-future in order to mark tense.

*Vésh smízw mésh bát > Vésh na smízw mésh bát 'We build me a boat'

*Hann skotj spjót > Hann ya skotj spjót 'He throws a spear'

11. At this point, subject pronouns became redundant. Because it was more productive to retain the imperfective markers, which contained more semantic information and was thus more efficient, the language becomes pro-drop. Subject markers were now only used for emphasis.

Ta ḫdum al løjusøjumann 'You serve the chief.'

Na smízw mésh bát 'We build me a boat'

Ya skotj spjót 'He throws a spear'

(A: Ḫer ya skotj spjót? B: Hann ya skotj spjót. - 'A: Who throws a spear? B: He throws a spear.')

12. Because the imperfective was most commonly used, it could be assumed that an unqualified verb -- a verb without an auxiliary -- is imperfective. To improve efficiency, a semantic shift occurs in which the imperfective aspect was shifted from the personal marker to the verb stem.

Kha ya vinn Yechya? Fer e wa sjokw - 'What is John doing? He is heading to the market.'

13. The personal markers thus underwent semantic loss and now referred solely to person. As such, they became reanalyzed as subject pronouns.

A: Khur etj khobz? B: Na - 'A: Who eats flatbread? B: We do'

14. The Norse pronouns stuck around for secondary functions, such as clarification and emphasis.

§6 Borrowing Morphology in Your Constructed Language

Now that we have reviewed the theoretical background of morphological borrowing, and have demonstrated it with Marshlandic, you are ready to apply it to your constructed language. Using the information provided in this post, follow these steps for borrowing morphology into your constructed language:

1. Identify which language will receive the morphology.

2. Identify a community bilingual in both languages, but whose primary or most prestigious language will be the recipient language. This community, the Forebearers, will introduce the change.

3. Decide whether the Forebearers have enough prestige and networking outside of their community to spread their borrowing throughout the language. If not, the result will only be dialectal.

4. Write down a description of the social relations between speakers in this community who primarily use the recipient language, and those who primarily use the donor language. Describe also how they perceive one another, especially in terms of stereotypes. Consider the cultural facets each community is known for. Also describe their typical interactions with each other -- i.e., in what social contexts do they interact with each other?

5. With the description you have written in mind, consider in what social contexts the Forebearers would codeswitch for efficiency. That is, in what cases is communication easiest if the Forebearer uses the donor language instead of his primary language? Write these down. See "Domains of Lexical Borrowing" for more information.

6. Consider these situations, and come up with examples of codeswitching. Identify in these examples common expressions or morphological uses that might prove more efficient in the donor language than in the recipient language. For instance, the word duklipes in a constructed language communicates, with less effort, its English translation, "the thing that was picked off the tree." It is formed by adding the prefix du- to the participle klipes "picked off the tree," and this prefix occurs often in codeswitching. It would be more efficient for an English speaker to say "dupicked" than "the thing that was picked," and is thus a candidate for morphological borrowing.

7. Now that you have identified what morphological features a Forebearer might borrow, consider the information in §3. Group and write down the applicable theories in three categories: theories that enable borrowing, theories that inform the borrowing process, and theories that constrain or prevent borrowing.

8. Review what you've written down in step 7, and decide whether the morphological borrowing you're considering is possible or not. If so, explain to yourself how and then move on to step 9. If not, stop here.

9. Check the borrowing against the directionality of morphological change in §2. If the borrowing remains plausible, write down how the theories of directionality informs how the borrowing will occur.

10. Review what you've written down in steps 7 and 9, and review §1. Describe what seems to be the most plausible scenario for how the borrowing will be incorporated into the language.

11. On a new piece of paper, write down a likely example of the Forebearers' codeswitching that uses the morphological feature that will be borrowed. The examples you wrote down in step 5 should work. Then, show step-by-step how that feature becomes incorporated into the Forebearers' language, rewriting the sentence for each step.

12. Test the result by using it in other sentences. If it is difficult to apply to other sentences, consider whether its actual function has changed by its borrowing. If you determine it retains its original function, it will not be borrowed after all because the ability to conform it to the language is too constrained.

13. Consider how this will change the structure of the Forebearers' language. Where is there overlap with existing morphemes? What is redundant? Review §1, and describe the likely morpheme change(s) to the affected morphemes. Then show the likely progression of this change step-by-step.

Have you tried these steps with your own constructed language? Contact me, and your constructed language will be featured in this post as an example!

§7 Bibliography

Lyle Campbell. Historical Linguistics: An Introduction (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013).

Frederic W. Field. Linguistic Borrowing in Bilingual Contexts (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co., 2002).

Jeanette Sakel and Yaron Matras. Grammatical Borrowing in Cross-linguistic Perspective (New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 2007).

Frank Seifart. "The principle of morphosyntactic subsystem integrity in language contact." Diachronica 29.4 (December 2012): 471-504.