Chinese tones and tonogenesis

-

The Peloric Orchid

- Niš

- Posts: 12

- Joined: Fri Nov 16, 2007 11:17 pm

- Location: Michigan

Chinese tones and tonogenesis

I'm want to apply sound changes to my conlang so that tonogenesis can occur. I want to do something more complicated than "losing voiced/unvoiced consonants causes low/high tones."

I found an interesting quote: "The classic view for Chinese is that the loss of a final glottal stop yielded the medieval shang tone, while loss of final -s and/or -h yielded the qu tone. The ping tone would have arisen when neither consonant was present, and ru would simply comprise syllables having various obstruent finals, usually posited as -p, -t, or -k, though some authorities envisage other such stops. This view, with individual variations, is rather widely held by people who work on Old Chinese today." (http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=4906)

However, I can't find any sources that both a) describe the tones in a way that is meaningful to me as a non-student of Chinese and b) use these tone names. I've come across English names like "entering" and "departing" which are sort of meaningless to me as well as numbers for them, but the Chinese names they offer are literally the Chinese words for 1-4 and tone, instead of this shang/qu/ping/ru business.

Could someone in the know please enlighten me? Thanks!

I found an interesting quote: "The classic view for Chinese is that the loss of a final glottal stop yielded the medieval shang tone, while loss of final -s and/or -h yielded the qu tone. The ping tone would have arisen when neither consonant was present, and ru would simply comprise syllables having various obstruent finals, usually posited as -p, -t, or -k, though some authorities envisage other such stops. This view, with individual variations, is rather widely held by people who work on Old Chinese today." (http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=4906)

However, I can't find any sources that both a) describe the tones in a way that is meaningful to me as a non-student of Chinese and b) use these tone names. I've come across English names like "entering" and "departing" which are sort of meaningless to me as well as numbers for them, but the Chinese names they offer are literally the Chinese words for 1-4 and tone, instead of this shang/qu/ping/ru business.

Could someone in the know please enlighten me? Thanks!

The tenor may get the girl, but the bass gets the woman.

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

The very simple of it is:

-ʔ deletes leaving high tone, -s>-h deletes leaving falling tone

Initial voiced consonants devoice, lowering the tone

There's all kinds of complexities in terms of the specifics, though, as quickly becomes obvious when you look at charts like the ones found here (the first of which also shows more clearly what happened using the Chinese terms). There's correlations such that a given tone will be used for a set of words, across dialects, but what that tone sounds like is all over the place.

-ʔ deletes leaving high tone, -s>-h deletes leaving falling tone

Initial voiced consonants devoice, lowering the tone

There's all kinds of complexities in terms of the specifics, though, as quickly becomes obvious when you look at charts like the ones found here (the first of which also shows more clearly what happened using the Chinese terms). There's correlations such that a given tone will be used for a set of words, across dialects, but what that tone sounds like is all over the place.

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

All I can say is that tonogenesis will likely be hugely different from that of Chinese if your language is a primarily multisyllabic setup where you can have five or six unstressed syllables in a row. Then you will have a lot of other processes that operate on units larger than just a single syllable, and can play with tools like tone sandhi and downstep where the same morpheme can change to different tones depending on whether it precedes or follows the stressed syllable. One idea I like is that a sequence of two identical vowels can change into a long vowel with either a rising or a falling tone, but never a level one, because one of the two identical vowels would have been sandhi'ed up to a higher tone level than the other (in my conlangs, it is always the stressed vowel; and if two unstressed identical vowels meet up, the second one becomes stressed even if there is already a stressed syllable in the word ... thus laă "spill" becomes lá, where á is a rising tone).

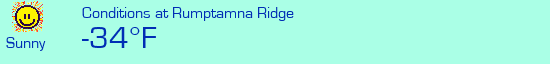

And now Sunàqʷa the Sea Lamprey with our weather report:

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

Yeah, I was going to mention that too. I think I remember someone on this board once mentioning that to them, the syllabic nasals found in Dutch Low Saxon sound (exactly?) like the other nasals, except for their falling tone, in words such as (my example) /ben/ vs /be.n̩/.Publipis wrote:One idea I like is that a sequence of two identical vowels can change into a long vowel with either a rising or a falling tone...

χʁɵn̩

gʁonɛ̃g

gɾɪ̃slɑ̃

gʁonɛ̃g

gɾɪ̃slɑ̃

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

You should treat them as merely names. The actual realisation of these tones has (of course) shifted over time. For instance, in Mandarin, the "rising" (shang) tone is falling-rising, and in Cantonese the "departing" (qu) tone is actually level.The Peloric Orchid wrote:However, I can't find any sources that both a) describe the tones in a way that is meaningful to me as a non-student of Chinese and b) use these tone names. I've come across English names like "entering" and "departing" which are sort of meaningless to me as well as numbers for them, but the Chinese names they offer are literally the Chinese words for 1-4 and tone, instead of this shang/qu/ping/ru business.

書不盡言、言不盡意

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

Since no one's listed them all, the four Middle Chinese tones are

píng 'level'

shǎng 'rising'

qù 'departing'

rù 'entering'

Karlgren though that the first three were level, rising, and falling; rù is comprised of syllables originally ending in a stop. This was based on the names and is highly speculative. The names exemplified the tonal categories, so they were not necessarily very explanatory.

Tonal development since Middle Chinese is complicated. In Mandarin:

píng : after voiceless initials tone 1, else tone 2 (note: 'voiceless' in MC, not the modern language)

tone 1, else tone 2 (note: 'voiceless' in MC, not the modern language)

shǎng : after voiced obstruents tone 4, else tone 3

tone 4, else tone 3

qù tone 4

tone 4

rù can go any tone

Thus knowing the Mandarin tone does not tell you the MC tone.

píng 'level'

shǎng 'rising'

qù 'departing'

rù 'entering'

Karlgren though that the first three were level, rising, and falling; rù is comprised of syllables originally ending in a stop. This was based on the names and is highly speculative. The names exemplified the tonal categories, so they were not necessarily very explanatory.

Tonal development since Middle Chinese is complicated. In Mandarin:

píng : after voiceless initials

shǎng : after voiced obstruents

qù

rù can go any tone

Thus knowing the Mandarin tone does not tell you the MC tone.

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

Ping shang qu ru are just names in the sense that people labeled the four tones in MC with four Chinese characters having the respective tones. So the tone "ping" or "leveling" is called "ping" or "leveling" simply because the corresponding character had this tone in MC. Of course you can argue that people did not just randomly pick four characters as the four tones' names but intended to mean something by the choice, so say "ping" is most likely a flat tone and so on.

Just PS: the rule for ru tone to be redistributed into the other tones for the Beijing dialect is:

Syllables starting with:

MC voiceless obstruents--apparently random, but some have argued that this randomness is a result of dialect contact and multiple linguistic "layers" that coexist in the dialect. Many people have attempted to find patterns and rules.

MC voiced obstruents--basically all went to tone 2 of Beijing dialect, with only a few exceptions for some formal words, which went to tone 4.

MC (voiced) sonorants--tone 4.

That said, in EMC the tone ru is just composed of phonologically toneless syllable. All the syllables ending in stops in EMC are said to have ru tone; syllables that do not can have one of ping, shang, and qu. In many dialects, later developments have let such syllables to be phonologically tonal.

Just PS: the rule for ru tone to be redistributed into the other tones for the Beijing dialect is:

Syllables starting with:

MC voiceless obstruents--apparently random, but some have argued that this randomness is a result of dialect contact and multiple linguistic "layers" that coexist in the dialect. Many people have attempted to find patterns and rules.

MC voiced obstruents--basically all went to tone 2 of Beijing dialect, with only a few exceptions for some formal words, which went to tone 4.

MC (voiced) sonorants--tone 4.

That said, in EMC the tone ru is just composed of phonologically toneless syllable. All the syllables ending in stops in EMC are said to have ru tone; syllables that do not can have one of ping, shang, and qu. In many dialects, later developments have let such syllables to be phonologically tonal.

Last edited by Seirios on Sat Jan 03, 2015 3:36 am, edited 8 times in total.

Always an adventurer, I guess.

-

Tone: Chao's notation.

Apical vowels: [ɿ]≈[z̞̩], [ʅ]≈[ɻ̞̩], [ʮ]≈[z̞̩ʷ], [ʯ]≈[ɻ̞̩ʷ].

Vowels: [ᴇ]=Mid front unrounded, [ᴀ]=Open central unrounded, [ⱺ]=Mid back rounded, [ⱻ]=Mid back unrounded.

-

Tone: Chao's notation.

Apical vowels: [ɿ]≈[z̞̩], [ʅ]≈[ɻ̞̩], [ʮ]≈[z̞̩ʷ], [ʯ]≈[ɻ̞̩ʷ].

Vowels: [ᴇ]=Mid front unrounded, [ᴀ]=Open central unrounded, [ⱺ]=Mid back rounded, [ⱻ]=Mid back unrounded.

-

The Peloric Orchid

- Niš

- Posts: 12

- Joined: Fri Nov 16, 2007 11:17 pm

- Location: Michigan

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

So it entering tone/tone 4 the one that goes up and down?

The tenor may get the girl, but the bass gets the woman.

-

The Peloric Orchid

- Niš

- Posts: 12

- Joined: Fri Nov 16, 2007 11:17 pm

- Location: Michigan

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

Sort of unrelated, but do languages ever lose tones? What other sounds changes happen/would happen in the even a language lost it's tones?

The tenor may get the girl, but the bass gets the woman.

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

complete deletion, or, possibly, some kind of vowel change

I guess some feature of tone could conceivably carry over to the consonants as, say, breathy or glottal voice but I've never heard of that happening

I guess some feature of tone could conceivably carry over to the consonants as, say, breathy or glottal voice but I've never heard of that happening

Slava, čĭstŭ, hrabrostĭ!

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

Yeah I think the most common change is for the tones to completely disappear leaving no effect on the sounds around them. However, I imagine that it is common that tones are more likely to disappear from a language that is undergoing rapid change of some other type. For example, maybe a stress accent appears which causes other syllables to bleed together and lose their tonal distinctiveness. This would mean that only the stressed syllable carries tone, thus making it a pitch accent language. And in a pitch accent language where the average word is long, tone can disappear entirely without much loss of intelligiblity. e.g. Greek and ancient SAnskrit. That would be more plausible I think than all the speakers of a Chinese-like language suddenly just merging all the tones together. In fact, the Shanghai dialect of Chinese is usually analyzed as being a pitch accent system because only the first syllable of a word carries a distinctive tone .... the other syllables are all 100% predictable from the first syllable. However Chinese does not have a lot of long words.

Sunàqʷa the Sea Lamprey says:

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

Entering tone is different than tone 4. Tone 4 is "departing" or qu, and in Beijing and Standard Chinese is falling (51 - starting at highest pitch 5 and dropping to lowest 1). Entering tone is originally a non-tone from a syllable ending in a stop, later redistributed into one of the other four tones once the stops reduced to ʔ>zero, or as a fifth tone, depending on dialect. One of the Wikipedia charts I linked to in my first post shows the outcomes of the entering tone in different Mandarin dialects; in Beijing dialect/Standard Chinese, the entering tone syllables ending in a sonorant all did become Tone 4/qu/departing, which I think is maybe where you got mixed up.The Peloric Orchid wrote:So it entering tone/tone 4 the one that goes up and down?

As for losing tone, it's going to depend in part on how the tones are realized. In Standard Chinese, for example, there's 55, 35, 214, and 51 (5 being highest pitch, 1 lowest). Northern Vietnamese, on the other hand, has a set of 33, 21 with breathy voice, 31(3) with stiff voice (optionally harsh voice as well), 35 with strong medial creakiness or even full glottal closure, 35 with stiff voice, and 21 with rapidly creakiness until it ends in a glottal stop. In Vietnamese, you'd certainly expect expect phonation differences to affect how exactly the tones collapsed into something else (and probably length as well, the 21+breathy is generally the longest, and the 21+glottal stop the shortest). Really you probably wouldn't expect such a system to collapse quickly, while a much simpler high-low system of tones might be replaced by stress accent rather quickly.

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

The Peloric Orchid wrote:Sort of unrelated, but do languages ever lose tones? What other sounds changes happen/would happen in the even a language lost it's tones?

R.Rusanov wrote:complete deletion, or, possibly, some kind of vowel change

I guess some feature of tone could conceivably carry over to the consonants as, say, breathy or glottal voice but I've never heard of that happening

Sorry for the necromancy, but as I looked through the jōyō kanji table, I noticed that MC tones probably conditioned sound changes. Specifically, while MC voiced obstruents all devoiced in Mandarin, those in the level tone became aspirated, while those in departing tone became tenuis. This may be a confirmation bias though, and I've yet to find enough characters in the rising and entering tone to find conclusive evidence.Soap wrote:Yeah I think the most common change is for the tones to completely disappear leaving no effect on the sounds around them. However, I imagine that it is common that tones are more likely to disappear from a language that is undergoing rapid change of some other type. For example, maybe a stress accent appears which causes other syllables to bleed together and lose their tonal distinctiveness. This would mean that only the stressed syllable carries tone, thus making it a pitch accent language. And in a pitch accent language where the average word is long, tone can disappear entirely without much loss of intelligiblity. e.g. Greek and ancient SAnskrit. That would be more plausible I think than all the speakers of a Chinese-like language suddenly just merging all the tones together. In fact, the Shanghai dialect of Chinese is usually analyzed as being a pitch accent system because only the first syllable of a word carries a distinctive tone .... the other syllables are all 100% predictable from the first syllable. However Chinese does not have a lot of long words.

As of now, I've only found one character that split due to tones: 藏 *dzɑŋ, "to store, hide" in level tone, "storage" in departing tone, and the Mandarin reflexes are cáng and zàng respectively.

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

This is a regular sound change. See e.g. here. Another example is 重.M Mira wrote:Sorry for the necromancy, but as I looked through the jōyō kanji table, I noticed that MC tones probably conditioned sound changes. Specifically, while MC voiced obstruents all devoiced in Mandarin, those in the level tone became aspirated, while those in departing tone became tenuis. This may be a confirmation bias though, and I've yet to find enough characters in the rising and entering tone to find conclusive evidence.

As of now, I've only found one character that split due to tones: 藏 *dzɑŋ, "to store, hide" in level tone, "storage" in departing tone, and the Mandarin reflexes are cáng and zàng respectively.

書不盡言、言不盡意

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

For an alternative to Chinese, look at tonogenesis in Athabaskan. Most or all (I can't remember) of the Athabaskan languages have tone, but the cognates have different or even exactly reversed tones among the different languages. This is because Proto-Athabaskan had final glottalised consonants (ejectives) which lost their glottalisation, leaving tone in its place, and the different daughter languages each got different tones from this.

Another alternative is Slavic. There was a lot of stress shifting in Common Slavic; it's pretty complicated, but my understanding is that stress tended to shift away from middle syllables towards the first or last syllables, and as stress shifted, it created a pitch accent on the newly stressed syllable, the exact pitch contour depending on where the stress shifted from and which particular wave of sound changes it occurred in.

Another alternative is Slavic. There was a lot of stress shifting in Common Slavic; it's pretty complicated, but my understanding is that stress tended to shift away from middle syllables towards the first or last syllables, and as stress shifted, it created a pitch accent on the newly stressed syllable, the exact pitch contour depending on where the stress shifted from and which particular wave of sound changes it occurred in.

Re: Chinese tones and tonogenesis

Also Mohawk, which got falling tone instead of rising from loss of final glottal stops/fricatives. The moral of the story seems to be that loss of final laryngeals usually results in rising tone, unless the laryngeal first imparts creakiness to the preceding vowel.Buran wrote:For an alternative to Chinese, look at tonogenesis in Athabaskan. Most or all (I can't remember) of the Athabaskan languages have tone, but the cognates have different or even exactly reversed tones among the different languages. This is because Proto-Athabaskan had final glottalised consonants (ejectives) which lost their glottalisation, leaving tone in its place, and the different daughter languages each got different tones from this.

"But if of ships I now should sing, what ship would come to me,

What ship would bear me ever back across so wide a Sea?”

What ship would bear me ever back across so wide a Sea?”